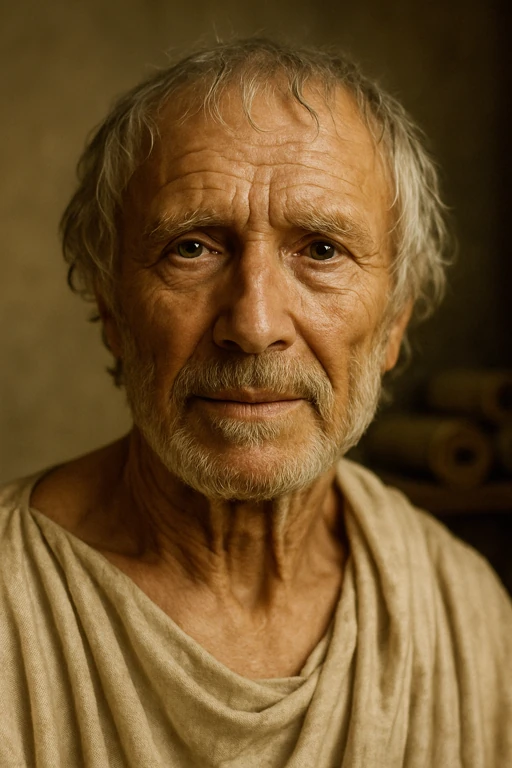

Seneca

Quotes & Wisdom

Lucius Annaeus Seneca: Stoic Sage in a Turbulent Empire

Few figures embody the paradoxes of power and principle quite like Seneca. A Roman philosopher, playwright, and statesman of the 1st century CE, Seneca lived at the volatile intersection of Stoic ideals and imperial politics. As tutor and advisor to Emperor Nero, he wielded immense influence—yet his writings often speak of simplicity, virtue, and inner freedom. This tension between worldly entanglement and philosophical detachment forms the heart of his story.

Seneca's blend of moral introspection, sharp rhetoric, and psychological acuity still resonates, especially in an age grappling with burnout, ethical leadership, and resilience. His letters and essays offer tools not just for survival, but for serenity amid chaos.

In this profile, we'll explore the Roman world that forged Seneca's Stoicism, the personal contradictions that shadowed his life, the literary brilliance that carried his voice through the centuries, and the enduring appeal of his practical wisdom.

Context & Background

Born around 4 BCE in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba, Spain), Seneca came of age in the early Roman Empire during a period of consolidation following decades of civil war. Augustus had just transformed the crumbling Republic into a tightly controlled autocracy. By the time Seneca was active in politics, emperors like Caligula and Claudius embodied both the grandeur and peril of centralized power.

Seneca's father, Seneca the Elder, was a rhetorician who moved the family to Rome, ensuring his son received elite education in grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy. Stoicism, imported from Greece and adapted for Roman sensibilities, became the guiding framework of Seneca's intellectual life. This philosophy emphasized rational control over emotion, alignment with nature, and the pursuit of virtue over external success.

But Stoicism in Rome wasn't just theoretical—it was a toolkit for navigating a dangerous world. With emperors prone to paranoia and brutality, being too honest or too popular could mean death. The philosopher had to walk a tightrope between truth and survival.

Seneca's formative years also coincided with growing tensions between traditional Roman values and Hellenistic influences. As imperial wealth expanded, so did moral anxiety over luxury, ambition, and decadence—concerns that surface again and again in Seneca's writings.

Seneca's most famous works are his moral essays and 124 letters to Lucilius, composed later in life while semi-retired. These letters—half correspondence, half philosophical treatise—address anxiety, wealth, grief, anger, and the pursuit of peace. Written in a warm, direct style, they offer solace and guidance without ever feeling preachy.

His emphasis on short, memorable aphorisms helped popularize Stoicism for generations. Phrases like "We suffer more often in imagination than in reality" capture the spirit of cognitive reframing and emotional regulation long before modern psychology did.

The letters also reflect Seneca's own struggles. He was not a cloistered sage but a man who had courted imperial favor, grown fabulously wealthy, and navigated the treacherous politics of Nero's court. His writings often wrestle with hypocrisy, compromise, and the gap between ideal and reality.

This self-awareness gives his work lasting relevance. Seneca doesn't offer abstract perfection—he models a philosophy lived amid contradiction.

Seneca's political career reached its apex when he became tutor—and later advisor—to the young Emperor Nero. For several years, he was credited with steering Nero toward a more balanced rule. He co-authored early speeches and tried to instill a Stoic sense of duty.

Yet as Nero's reign grew more violent and erratic, Seneca's position became morally untenable. While he attempted to retire, Nero refused. Ultimately, Seneca was implicated in the Pisonian conspiracy to assassinate Nero—a charge whose legitimacy remains debated. Ordered to take his own life in 65 CE, Seneca died in the Roman tradition of stoic suicide.

His involvement with Nero remains the most contested aspect of his legacy. Was he a principled advisor trying to restrain a tyrant—or a compromised intellectual who accepted luxury and power while espousing simplicity?

The truth may be both. Seneca's life suggests the limits of philosophy when confronted with raw power. It also underlines a theme in his writing: that virtue is a struggle, not a state.

Beyond essays and letters, Seneca was a prolific playwright. His tragedies, written in Latin and modeled on Greek originals, dealt with themes of vengeance, fate, madness, and the psychological disintegration of power—eerily prescient given his political entanglements.

His dramatic works, including Phaedra, Thyestes, and Medea, were more rhetorical than performative, likely intended for recitation rather than stage. Yet they had a profound influence on Renaissance and Elizabethan drama, especially on writers like Shakespeare.

Seneca's use of intense soliloquies and moral conflict foreshadowed the inner turmoil that later Western literature would explore. His tragedies echo the dark grandeur of the world he inhabited, making him not just a moralist, but a dramatist of the human condition.

Seneca was a vegetarian, believing in the kinship of all living beings—a position unusual in Roman society and perhaps tied to his Stoic beliefs about nature and restraint. He also had frequent health issues, including bouts of asthma so severe he reportedly viewed them as practice for death.

His relationship with his wife, Pompeia Paulina, is remembered for her loyalty: when Seneca was ordered to die, she attempted to join him in suicide, only surviving after imperial reprieve.

Despite his immense wealth—including sprawling estates and luxury villas—he frequently condemned extravagance. This paradox was not lost on critics, ancient or modern. Yet Seneca addressed it directly in his writings, arguing that it is not possession, but dependence on wealth, that corrupts.

He also had a keen interest in natural science. His treatise Natural Questions examined phenomena from comets to earthquakes, blending empirical curiosity with metaphysical reflection. This lesser-known work reveals a mind eager to reconcile Stoicism with the expanding Roman worldview.

Ultimately, Seneca remains compelling not because he was flawless, but because he was flawed—and conscious of those flaws. He invites us not to follow a saint, but to walk alongside a fellow struggler in search of wisdom.

Seneca Quotes

Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity

We suffer more often in imagination than in reality

There is no easy way from the earth to the stars

As is a tale, so is life: not how long it is, but how good it is, is what matters

Every new beginning comes from some other beginning's end

He who is brave is free

Life is long if you know how to use it

The greatest obstacle to living is expectancy, which hangs upon tomorrow and loses today

If you live according to nature, you will never be poor; if you live according to opinion, you will never be rich

It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor

What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears

While we wait for life, life passes

Sometimes even to live is an act of courage

Fate leads the willing and drags along the reluctant

It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare; it is because we do not dare that things are difficult

The part of life we really live is small, for all the rest is not life, but merely time

Anger, if not restrained, is frequently more hurtful to us than the injury that provokes it

No man was ever wise by chance

They lose the day in expectation of the night, and the night in fear of the dawn

We are more often frightened than hurt; and we suffer more from imagination than from reality

Nothing is more honorable than a grateful heart

Associate with people who are likely to improve you

The bravest sight in the world is to see a great man struggling against adversity

If you would judge, understand

One hand washes the other

No one can live happily who has regard to himself alone

Wherever there is a human being, there is an opportunity for kindness

The greatest wealth is a poverty of desires

Leisure without books is death

It is better to conquer our grief than to deceive it

Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by rulers as useful

He who spares the wicked injures the good

The wise man is neither raised up by prosperity nor cast down by adversity

To wish to progress is the largest part of progress

If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favorable

The difficulty comes from our lack of confidence

It is quality rather than quantity that matters

Most powerful is he who has himself in his own power

Fire tests gold, suffering tests brave men

What fortune has made yours is not your own

Life is warfare

As long as you live, keep learning how to live

The pressure of adversity does not affect the mind of the brave

No man is crushed by misfortune unless he has first been deceived by prosperity

You act like mortals in all that you fear, and like immortals in all that you desire

Begin at once to live, and count each separate day as a separate life

The good things of prosperity are to be wished; but the good things that belong to adversity are to be admired

He who has made a fair compact with poverty is rich

A gem cannot be polished without friction, nor a man perfected without trials

It is not that we have so little time but that we lose so much

The greatest power we have is that we get to choose our attitude

We should every night call ourselves to an account

If you want to be loved, love

All cruelty springs from weakness