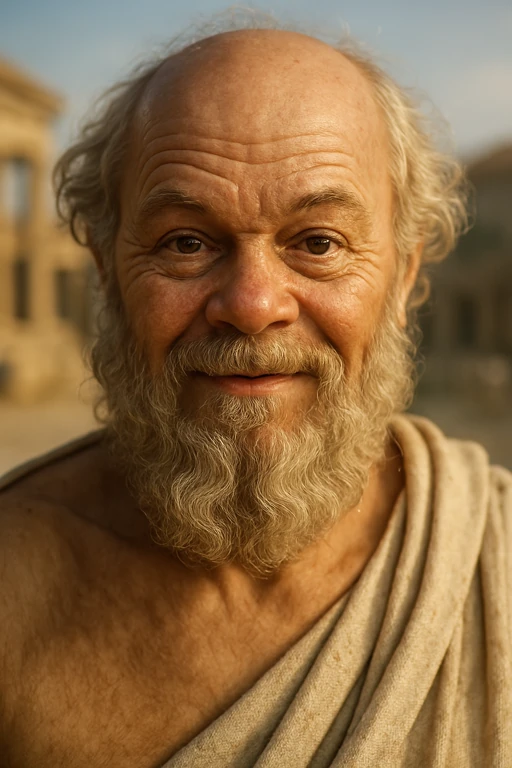

Socrates

Quotes & Wisdom

Socrates: The Relentless Seeker of Truth

Few figures loom larger over the landscape of Western thought than Socrates, the unyielding Athenian who made a career — and enemies — out of asking inconvenient questions. Not a conventional scholar nor a prolific writer, Socrates instead became the embodiment of a new kind of inquiry: relentless, methodical, and often unsettling. Operating in the bustling, volatile heart of 5th-century BCE Athens, he challenged assumptions, punctured arrogance, and pushed his fellow citizens — and ultimately, the entire course of philosophy — toward deeper reflection.

Despite leaving no writings of his own, the shadow of Socrates stretches across centuries, inspiring countless thinkers and movements. His method, legacy, and the dramatic circumstances of his death remain topics of fascination and debate today. In this profile, we'll journey through the world that shaped him, his philosophical revolution, the high-stakes drama of his trial, and the enduring mystery that still surrounds the man behind the myth.

Context & Background

The Athens of Socrates' youth was a city on the rise — bursting with new wealth, democratic fervor, and artistic innovation. Following its critical role in the Greco-Persian Wars, Athens had emerged as a leading power in Greece, boasting achievements in drama, architecture, and political thought that would echo through history. It was an era marked by figures like Pericles, whose vision turned Athens into a beacon of democracy and culture.

But under the surface, tensions simmered. Athens’ imperial ambitions bred resentment among its neighbors, setting the stage for the long and devastating Peloponnesian War against Sparta. The war would grind down Athenian pride and prosperity over decades, leaving the city's political ideals battered and its citizens weary and disillusioned.

Intellectually, the 5th century BCE was a time of radical experimentation. The Sophists — itinerant teachers such as Protagoras — roamed the Greek world, offering lessons in rhetoric, persuasion, and relativistic ethics, often for a hefty fee. To many, they symbolized the promise of success in a changing world; to others, like Socrates, they represented a dangerous decay of genuine inquiry into hollow cleverness.

The intersection of political instability and intellectual upheaval formed the crucible in which Socrates' ideas took shape. Questioning everything from the gods to the very meaning of virtue, he carved a unique path — one that would ultimately collide with the precarious sensitivities of his fellow citizens.

Socrates did not lecture from a podium or establish a formal school. Instead, he wandered the public spaces of Athens — the agora, workshops, and gymnasia — engaging anyone willing (or sometimes unwilling) to enter into dialogue. His conversations, immortalized by his student Plato, often began with seemingly simple questions that gradually revealed layers of ignorance and contradiction.

This method — later termed the "Socratic method" — was revolutionary. Rather than offering answers, Socrates sought to expose the gaps in others' knowledge, believing that true wisdom began with recognizing one's own ignorance. His approach, relentless and disarming, often embarrassed the proud and powerful, earning him both admiration and deep resentment.

To Socrates, philosophy was not an abstract pastime but a moral imperative. He likened himself to a gadfly stinging the sluggish horse of Athens, keeping it awake and alive. Far from enriching himself, Socrates lived simply, eschewing material wealth and political office, embodying the examined life he so passionately advocated.

In 399 BCE, the patience of Athens snapped. Socrates was charged with "impiety" — corrupting the youth and introducing new gods. Beneath these formal accusations lay deeper anxieties: the fear that Socrates, by undermining traditional beliefs and social norms, had contributed to the instability and political disasters that had rocked Athens.

The trial, as depicted in Plato’s Apology, was a tense confrontation between individual conscience and civic authority. Socrates, unapologetic and even defiant, used the occasion to reaffirm his mission rather than curry favor with the jury. Famously declaring that "the unexamined life is not worth living," he chose principle over survival.

Ultimately convicted, Socrates was sentenced to death by drinking hemlock. His calm and dignified acceptance of his fate elevated him, in the eyes of later generations, to a martyr for truth and intellectual freedom. Yet for his contemporaries, the execution was both an assertion of communal authority and a warning about the dangers of radical questioning.

Though Socrates himself wrote nothing, his intellectual descendants — foremost among them Plato and Xenophon — ensured that his thought would not be buried alongside him. Plato, in particular, made Socrates the central figure of his dialogues, blending historical memory with philosophical development.

Through these portrayals, Socrates became the symbolic founder of Western philosophy. His insistence on reasoned dialogue, ethical inquiry, and the pursuit of truth at any personal cost became the bedrock principles for future philosophical traditions. His influence reverberates through Aristotle, Descartes, and even Nietzsche, who, despite his criticisms, recognized Socrates’ seismic impact.

Beyond philosophy, Socrates' life invites enduring questions about the relationship between the individual and society, the nature of moral courage, and the responsibilities that come with freedom of thought. His death, paradoxically, secured his immortality.

Behind the towering symbol of Socratic wisdom was a man of curious contradictions. Socrates was physically unremarkable by the standards of his day — short, stocky, with bulging eyes and a snub nose — yet accounts describe a magnetic presence that captivated his listeners. He was known for extraordinary endurance, famously standing motionless for hours deep in thought, and for showing remarkable resilience in battle during the Peloponnesian War.

Socrates also maintained close, sometimes enigmatic, relationships. His marriage to Xanthippe, often portrayed as volatile, suggests a domestic life far removed from the serene philosopher image. His friendships spanned the political spectrum, including associations with both democratic supporters and oligarchic sympathizers — a complexity that would later fuel suspicions about his loyalty to Athens.

Notably, Socrates professed a kind of inner divine voice — his "daimonion" — that guided his actions, warning him against missteps but never dictating positive courses. This private spiritual experience, unusual and personal, perhaps illuminates his distinctive blend of rational inquiry and moral intuition.

These personal dimensions underscore the humanity behind the legend, reminding us that Socrates’ greatness lay not in perfection, but in an unrelenting commitment to live — and die — in accordance with his principles.

Socrates Quotes

The unexamined life is not worth living.

I know that I know nothing.

By all means marry; if you get a good wife, you'll become happy; if you get a bad one, you'll become a philosopher.

Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle.

The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.

Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.

Let him who would move the world first move himself.

Wonder is the beginning of wisdom.

To find yourself, think for yourself.

The way to gain a good reputation is to endeavor to be what you desire to appear.

Beware the barrenness of a busy life.

He who is not contented with what he has, would not be contented with what he would like to have.

I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think.

There is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance.

The secret of happiness, you see, is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less.

Strong minds discuss ideas, average minds discuss events, weak minds discuss people.

Be slow to fall into friendship, but when thou art in, continue firm and constant.

False words are not only evil in themselves, but they infect the soul with evil.

Understanding a question is half an answer.

Death may be the greatest of all human blessings.

Not life, but good life, is to be chiefly valued.

The greatest way to live with honor in this world is to be what we pretend to be.

Once made equal to man, woman becomes his superior.

The nearest way to glory is to strive to be what you wish to be thought to be.

Remember that there is nothing stable in human affairs; therefore avoid undue elation in prosperity, or undue depression in adversity.

Remember what is unbecoming to do is also unbecoming to speak of.

Employ your time in improving yourself by other men's writings, so that you shall gain easily what others have labored hard for.

Nature has given us two ears, two eyes, and but one tongue-to the end that we should hear and see more than we speak.

Think not those faithful who praise all thy words and actions, but those who kindly reprove thy faults.

Our prayers should be for blessings in general, for God knows best what is good for us.

Beauty is a short-lived tyranny.

Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live.

If all misfortunes were laid in one common heap whence everyone must take an equal portion, most people would be contented to take their own and depart.

From the deepest desires often come the deadliest hate.

The greatest blessing granted to mankind come by way of madness, which is a divine gift.

Living well and beautifully and justly are all one thing.

Life contains but two tragedies. One is not to get your heart's desire; the other is to get it.

Do not do to others what angers you if done to you by others.

When the debate is lost, slander becomes the tool of the loser.

The only good is knowledge and the only evil is ignorance.

No man has the right to be an amateur in the matter of physical training. It is a shame for a man to grow old without seeing the beauty and strength of which his body is capable.